The Bald Eagle

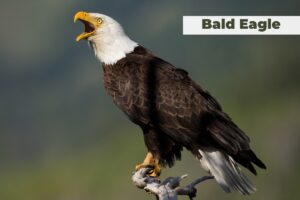

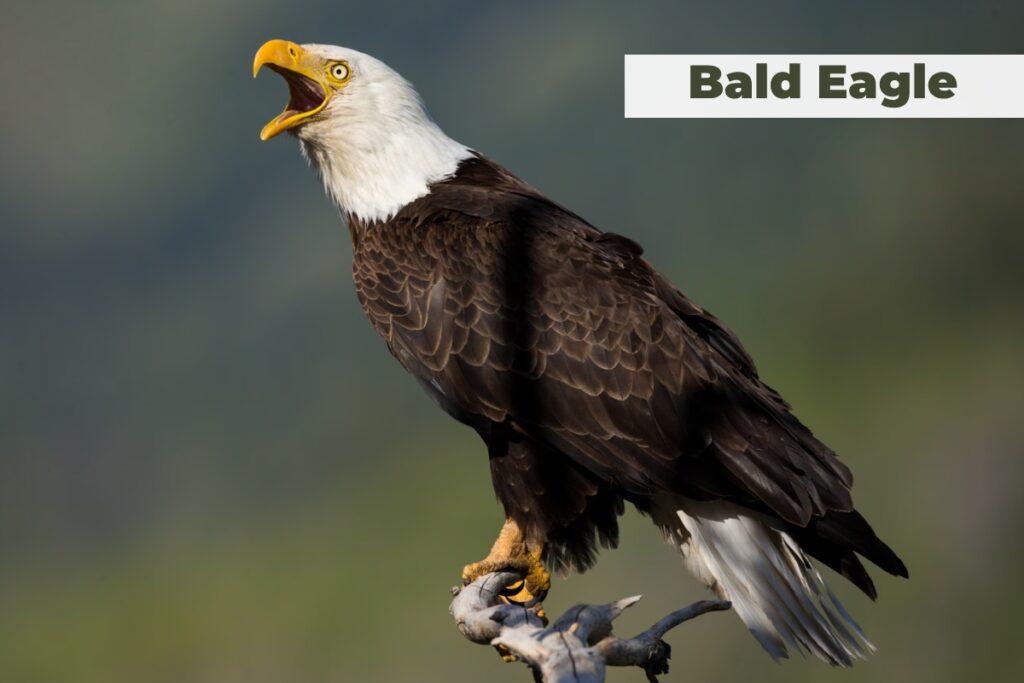

The Bald Eagle soars as a living emblem of freedom, its white head gleaming against the sky and its piercing cry echoing over rivers and forests.

Known scientifically as Haliaeetus leucocephalus, the Bald Eagle reigns as North America’s most iconic raptor, a sea eagle whose presence commands awe and respect.

With a wingspan stretching up to 8 feet and a history tied to both wilderness and human culture, the Bald Eagle captivates birdwatchers, conservationists, and patriots alike.

In this article, we explore the Bald Eagle’s biology, behavior, habitat, and significance, revealing why this majestic bird thrives as a symbol of resilience and wild beauty.

What Defines the Bald Eagle?

What sets the Bald Eagle apart? This large raptor, part of the Haliaeetus genus, boasts a striking appearance that evolves with age.

Adults sport a snowy white head and tail contrasting a chocolate-brown body, a look that emerges after four to five years.

Despite its name, the Bald Eagle isn’t bald—“bald” derives from the Old English balde, meaning white, a nod to its head feathers.

Juveniles start darker, with mottled brown and white plumage, resembling golden eagles until maturity clarifies their identity.

The Bald Eagle measures 70 to 102 centimeters (28 to 40 inches) in length, with females outweighing males at 5.6 to 6.3 kilograms (12.3 to 14 pounds) compared to 4.1 kilograms (9 pounds) for males.

Its wingspan, averaging 1.8 to 2.3 meters (5.9 to 7.5 feet), lets it glide effortlessly over water and land.

The Bald Eagle’s yellow beak hooks sharply for tearing prey, while its talons—larger in females—grip with crushing force.

Bright yellow eyes, fixed in shallow sockets, deliver vision eight times sharper than a human’s, spotting fish or carrion from a mile away.

This combination of size, strength, and sight defines the Bald Eagle as a top predator.

Unique Traits of the Bald Eagle: A Closer Look

The Bald Eagle’s allure lies in quirks that set it apart. Its white head, a badge of maturity, takes years to earn—juveniles sport a scruffy mix of brown and white, often mistaken for other raptors.

The Bald Eagle’s eyesight, with a 340-degree field of view, locks onto prey with laser focus, while its hearing detects subtle rustles.

Unlike songbirds, the Bald Eagle lacks a syrinx for complex calls—its high-pitched chatter belies its fierce image, a trait dubbed “laughably weak” by some.

The Bald Eagle’s talons wield 1,000 pounds of pressure per square inch, yet it rarely carries more than half its weight in flight.

Females outsize males by 25%, a reverse dimorphism rare among birds of prey, giving them an edge in nesting duties.

In winter, the Bald Eagle’s feathers puff for insulation, letting it perch unfazed in snow.

These traits—visual splendor, raw power, and subtle surprises—make the Bald Eagle a standout species.

Where Does the Bald Eagle Live?

The Bald Eagle thrives across North America, from Alaska’s icy coasts to Mexico’s northern deserts, favoring habitats near water—rivers, lakes, reservoirs, and seashores.

Fish dominate its diet, so the Bald Eagle builds massive nests, called eyries, in tall trees or on cliffs overlooking these aquatic hunting grounds.

In Alaska and Canada’s Pacific Northwest, where salmon abound, Bald Eagles concentrate in huge numbers, with thousands gathering during winter runs.

Even in arid regions like Arizona, the Bald Eagle adapts, nesting near scarce rivers.

Historically, the Bald Eagle roamed wherever large prey thrived, but its range shrank with human expansion.

Today, it spans 31 subspecies ranges across the continent, absent only from Hawaii.

Winter sees northern Bald Eagles migrate south, flocking to open water in states like Iowa or Missouri, while southern birds stay put.

Whether perched in a Douglas fir or soaring over the Chesapeake Bay, the Bald Eagle claims its domain with unmatched presence.

The Bald Eagle’s Hunting Skills

The Bald Eagle hunts with precision and opportunism, cementing its status as an apex predator.

Fish—salmon, herring, catfish—form its mainstay, snatched from the water’s surface with talons in a swift, shallow dive.

The Bald Eagle skims low, rarely submerging, and hauls prey weighing up to 1 kilogram (2 pounds) back to a perch.

Larger catches, like a 6.8-kilogram (15-pound) mule deer fawn—among the heaviest recorded loads—prove its strength, though such feats are rare.

Not every meal comes from hunting. The Bald Eagle scavenges carrion—dead fish, roadkill, or beached whales—especially in winter when live prey thins.

It also pirates food, harassing ospreys or gulls until they drop their catch, a behavior called kleptoparasitism.

This adaptability keeps the Bald Eagle fed year-round, whether swooping over a lake or scavenging a shoreline.

Its deep, barking cry—“kleek-kik-ik-ik”—often signals a hunt, a sound weaker than its fierce image suggests but unmistakable in the wild.

Bald Eagle Behavior: Social and Solitary

The Bald Eagle balances solitude with surprising sociability. Outside breeding season, it often roams alone, fiercely defending feeding territories with aerial chases or talon displays.

Yet, where food abounds—like Alaska’s Chilkat River salmon runs—hundreds of Bald Eagles gather, tolerating each other in loose flocks.

These communal feasts highlight the Bald Eagle’s pragmatism, prioritizing survival over isolation.

Courtship reveals the Bald Eagle’s dramatic flair. Pairs perform sky dances, locking talons mid-flight and cartwheeling toward the ground before breaking apart—a test of trust and agility.

Once bonded, Bald Eagles mate for life, returning to the same nest annually.

These behaviors blend independence with partnership, showcasing the Bald Eagle’s complex nature as both lone hunter and loyal companion.

Building the Nest: A Bald Eagle Stronghold

The Bald Eagle constructs nests that dwarf other birds’ efforts.

Using sticks, grasses, and moss, a pair builds an eyrie that can span 3 meters (10 feet) wide and weigh over 900 kilograms (1 ton)—the largest tree nests of any animal.

In Florida, one record-breaking Bald Eagle nest measured 6.1 meters (20 feet) deep.

Perched high in old-growth trees or on cliffs, these structures offer safety and a panoramic view for spotting prey.

Each year, the Bald Eagle adds to its nest, reinforcing it against wind and predators.

This dedication to nesting reflects the Bald Eagle’s investment in its future, a trait that helped it rebound from near extinction.

Bald Eagle Reproduction: Raising the Next Generation

The Bald Eagle’s life cycle unfolds with fierce dedication, as it nurtures its young through a meticulous process of mating, egg-laying, and fledging.

This raptor’s reproductive habits ensure the survival of its lineage, blending acrobatic courtship with steadfast parenting.

Chicks, born weak and downy, grow fast under the Bald Eagle’s care, fledging at 10 to 12 weeks.

The Bald Eagle’s commitment to its offspring mirrors its resilience, a trait that has carried it through centuries of challenges.

Courtship and Mating

The Bald Eagle kicks off its breeding season with a spectacle.

Pairs engage in aerial displays, soaring high before locking talons and tumbling earthward in a breathtaking cartwheel, pulling apart just before impact.

This dance, often seen in late winter, strengthens bonds and signals readiness to mate.

The Bald Eagle typically pairs for life, though a new partner steps in if one dies—a pragmatic approach to continuity.

Mating peaks from January to April in southern ranges, later in the north, with couples copulating on branches or near their eyrie.

The Bald Eagle’s nest becomes a hub of activity, as the pair prepares for eggs.

This ritual, both dramatic and tender, showcases the Bald Eagle’s blend of wild grace and domestic devotion, setting the stage for new life.

Eggs and Nestling Vulnerabilities

Female Bald Eagles lay one to three eggs. They usually lay two. The eggs appear in late winter or spring.

The eagles lay them a few days apart. Captive eagles can lay up to seven eggs. Each egg is a dull white oval.

It measures about 7.6 centimeters (3 inches) long. The male and female eagles take turns incubating the eggs, but the female incubates most often.

They do this for 34 to 36 days. While one parent incubates, the other hunts for food or gathers nesting material.

The Bald Eagle’s teamwork shines here, ensuring the eggs stay safe from cold and predators like ravens or gulls.

For the first two to three weeks of the nestling period, a parent eagle always protects the nest.

However, when food is scarce, eagle parents leave their nests more frequently, leaving their chicks vulnerable.

Bald eagles fiercely defend their nests, fighting off any intruders—even bears.

In one instance, an eagle knocked a black bear out of a tree as it attempted to climb toward a nest containing eaglets.

Many factors threaten eagle eggs and chicks. Nests may collapse, and chicks can starve.

Sibling rivalry and harsh weather often prove fatal. Predators pose another danger—gulls, ravens, crows, and magpies feed on eggs, while wolverines and fishers kill chicks in their nests.

Red-tailed hawks and owls hunt young eagles, and even adult eagles prey on the chicks of other eagles.

Bobcats, bears, and raccoons also target them. Though ground predators rarely climb trees, Arctic foxes have been known to snatch chicks from ground nests in Alaska.

The Eaglets of the Bald Eagle

Chicks hatch covered in light gray down, their eyes open but bodies helpless.

The parents feed them tirelessly, tearing fish into bite-sized pieces.

Sibling rivalry kills many chicks before they fledge. The oldest chick’s larger size and louder voice attract the parents’ attention.

In some cases, the older eaglet attacks and kills its younger siblings, especially when they are much smaller. Bald Eagles use this harsh survival tactic to survive.

Eaglets exhibit a record growth rate, gaining 170 grams (6.0 ounces) per day.

This represents the fastest growth rate observed in any North American bird species.

They are playful from the start, picking up sticks, moving them around, and even engaging in tug-of-war with one another.

They also practice grasping objects with their talons while stretching, flapping, and testing their wings in clumsy flights.

By eight weeks, the surviving eaglets become strong enough to lift their feet off the nest and begin flapping their wings, eventually taking flight.

The Process of Growth and Maturity

Typically, young eagles leave the nest between eight and fourteen weeks old, although their parents continue to guard and feed them for weeks, until they master hunting—often not until six months or more.

This extended care builds a strong next generation.

After that, juvenile eagles wander for about four years, during which time they search for food, develop adult feathers, and prepare for reproduction.

Sexual maturity arrives at 4 to 5 years, when that iconic white head emerges, marking the transition from juvenile to adult.

This slow growth reflects the Bald Eagle’s investment in longevity, a strategy that paid off in its recovery.

How Long Do Bald Eagles Live?

The bald eagle soars as a symbol of strength and freedom, but its lifespan—ranging from 15 to 30 years in the wild—hinges on a fragile interplay of challenges and resources.

From the moment an eaglet hatches to the day an adult surveys its domain, survival depends on more than just sharp talons and keen eyes.

Predators lurk, food can vanish, humans cast long shadows, and the environment itself can turn hostile.

Let’s explore the lifespan and key factors that determine how long these majestic birds thrive in the wild.

The Lifespan of Bald Eagles

The bald eagle lives a long life when conditions are favorable. In the wild, they have an average lifespan of about 15 to 30 years, though some can live longer under the right circumstances.

The oldest known wild bald eagle lived to be 38 years old. It was banded in 1977 in New York and found deceased in 2015.

In captivity, where they are protected from predators, food shortages, and harsh weather, they can live up to 50 years.

Factors Affecting Bald Eagle Lifespan:

Unlike many eagle species, bald eagles often live beyond two decades in the wild, with survival rates topping 50% during their first year.

In captivity, where threats are minimal, some studies even report a 100% survival rate for young eagles.

This iconic bird of prey, native to North America, owes its lifespan to a variety of factors.

Explore some of the key elements influencing the bald eagle’s longevity below:

Predation & Competition – While adult bald eagles have few natural predators, younger eagles may fall victim to larger birds of prey, such as great horned owls or other eagles.

Food Availability – A consistent food supply, mainly fish, is crucial for survival. Scarcity can lead to starvation, especially for young eagles.

Human Impact – Collisions with vehicles, electrocution from power lines, and lead poisoning (from ingesting lead fragments in hunted animals) are major threats.

Environmental Factors – Severe weather conditions, habitat destruction, and exposure to pesticides like DDT (which once led to population declines) also affect longevity.

Where eagles live and what they eat affect their lifespan. Adult eagles now live long lives because people no longer hunt them extensively.

According to a study in Florida, 100% of adult bald eagles survived each year, while in Alaska, 88% of adults survived—even after an Exxon Valdez oil spill harmed some of the eagles.

Studies on the Causes of Bald Eagle Deaths

A post-mortem examination conducted from 1963 to 1984 by the National Wildlife Health Center looked at 1,428 dead eagles.

The necropsies revealed that people shot 309 (22%) of them, traps killed 68 (5%), electrocution killed 130 (9%), poison killed 158 (11%), disease killed 31 (2%), starvation killed 110 (8%), and accidents killed 329 (23%).

The cause of death could not be determined for 293 (20%) of the eagles. Overall, the study shows that human-related factors were responsible for 68% of the eagle deaths.

Today, people shoot eagles much less because laws now protect them.

Additionally, a study by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service looked at 1,490 bald eagle deaths in Michigan from 1986 to 2017.

It showed that cars hit and killed 532 eagles (36%) while they ate roadkill, and lead poisoning from eating bits of lead ammo and fishing gear in carrion killed 176 eagles (12%).

Both causes of death went up a lot by the end of the study.

The Bald Eagle’s Ecological Role: Guardian of Balance

The Bald Eagle doesn’t just dominate the skies—it shapes ecosystems as a top predator and scavenger.

Its feeding habits ripple through food webs, influencing fish, birds, and even landscapes.

The Bald Eagle’s presence signals a healthy environment, making it a vital player in North America’s wild places.

Predator and Scavenger

The Bald Eagle preys primarily on fish—think salmon in Alaska or bass in the Midwest—swooping down to snatch them with pinpoint accuracy.

It also hunts waterfowl, rabbits, and small mammals when fish dwindle, adapting its menu to the season.

This predation keeps aquatic and terrestrial populations in check, preventing overabundance that could strain resources.

Scavenging sets the Bald Eagle apart from pure hunters like hawks. It feasts on carrion—dead deer, beached whales, or winter-killed fish—cleaning up nature’s leftovers.

By bullying smaller birds like ospreys into dropping their catches, the Bald Eagle redistributes food, indirectly feeding scavengers like crows that trail its kills.

This dual role as hunter and opportunist underscores the Bald Eagle’s ecological clout.

Indicator of Ecosystem Health

The Bald Eagle thrives where water runs clean and prey abounds, making it a barometer for environmental vitality.

Its decline in the mid-20th century, tied to DDT poisoning, flagged pesticide dangers—thin eggshells couldn’t withstand incubation, crashing populations.

The Bald Eagle’s rebound after DDT’s 1972 ban proves ecosystems can heal with human intervention.

Today, spotting a Bald Eagle over a river signals thriving fish stocks and unpolluted waters, a living testament to conservation’s power.

Interactions with Other Species

The Bald Eagle shares its realm with rivals and allies.

It clashes with golden eagles over territory, driving them away with dives and screeches. However, their ranges rarely overlap much—bald eagles stick to water, while golden eagles prefer uplands.

Ospreys lose fish to the Bald Eagle’s piracy, while ravens and gulls scavenge its scraps.

In winter flocks, the Bald Eagle tolerates its kind, a truce driven by abundance.

These dynamics weave the Bald Eagle into a broader tapestry, its influence felt across species.

The Bald Eagle in Culture: A National Icon

The Bald Eagle transcends biology to embody human ideals, its image etched into history and identity.

As America’s national bird, the Bald Eagle carries a legacy of freedom and strength, a symbol that resonates far beyond its feathers.

A Symbol of Independence

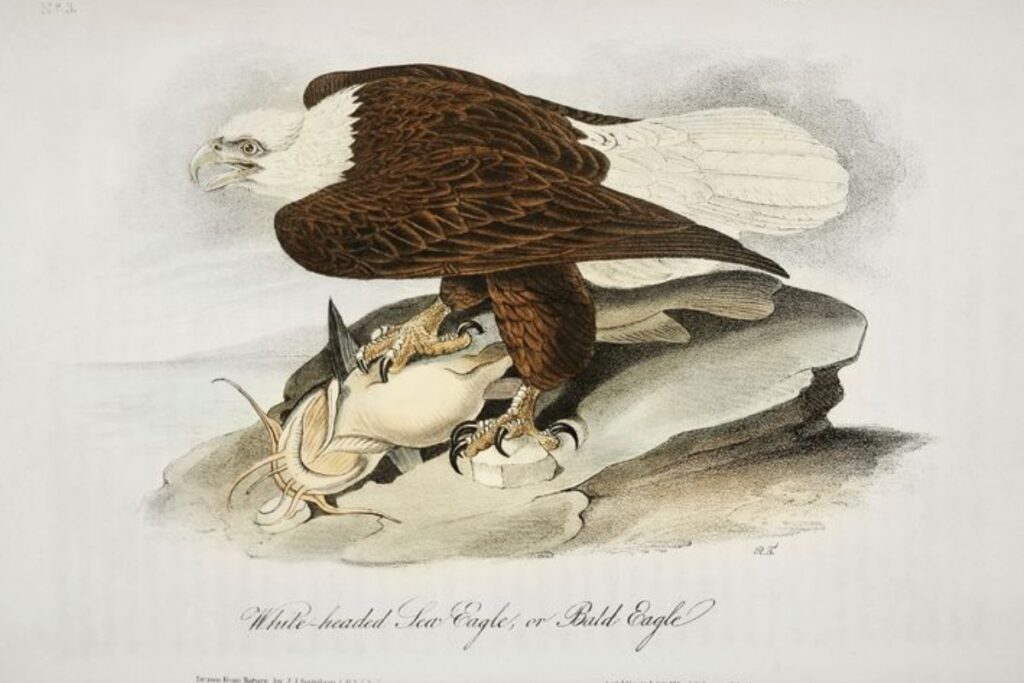

The Bald Eagle claimed its cultural throne on June 20, 1782, when the U.S. adopted it for the Great Seal.

Clutching an olive branch and arrows, the Bald Eagle represents peace and power—a choice championed by early leaders, though Benjamin Franklin famously favored the turkey.

Native Americans revered the Bald Eagle long before, with tribes like the Haida and Lakota using its feathers in ceremonies, seeing it as a messenger to the divine.

This dual heritage roots the Bald Eagle in both indigenous and national narratives.

Bald Eagles in Art and Media

Artists capture the Bald Eagle’s majesty—John James Audubon’s lifelike sketches immortalized it, while modern photographers chase its silhouette against snowy peaks.

In film and literature, the Bald Eagle soars as a wild spirit, from documentaries narrating its recovery to fiction casting it as a noble guardian.

Its cry, often dubbed over with a red-tailed hawk’s scream for drama, punctuates Hollywood scenes, amplifying its mystique.

The Bald Eagle graces coins, flags, and stamps, its white head a shorthand for American grit.

Conservation campaigns lean on this symbolism, rallying support with slogans like “Save the Bald Eagle”—a call that turned a near-lost icon into a thriving species.

Conservation of the Bald Eagle: A Triumph of Resilience

The Bald Eagle’s story nearly ended in tragedy, but its recovery stands as one of conservation’s greatest victories.

Once teetering on the edge of extinction, the Bald Eagle now soars across North America, a testament to human effort and nature’s tenacity.

This journey from peril to prosperity reveals why protecting the Bald Eagle matters—not just for the bird, but for the ecosystems and ideals it represents.

The Bald Eagle’s Decline

The Bald Eagle faced dire threats in the 20th century. By the 1700s, it thrived with an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 across the continent, but European settlement slashed its numbers.

Hunters shot Bald Eagles for sport or to protect livestock, while loggers felled old-growth nesting trees.

The real blow came with DDT, a pesticide introduced in the 1940s.

The Bald Eagle ingested DDT through contaminated fish, producing eggshells so thin they cracked under its weight.

By 1963, only 417 nesting pairs remained in the lower 48 states, a collapse that sounded alarms nationwide.

Lead poisoning from hunters’ ammunition, power line collisions, and habitat loss piled on the pressure.

The Bald Eagle’s plight mirrored a broader environmental crisis—its decline signaled polluted waters and a broken food chain, pushing it onto the endangered species list in 1967.

The Bald Eagle’s Comeback

Conservationists rallied to save the Bald Eagle, and their efforts paid off.

The 1972 ban on DDT in the U.S. marked a turning point—eggshells thickened, and hatching rates soared.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 shielded the Bald Eagle with legal muscle, banning hunting and protecting nests.

Biologists reintroduced Bald Eagles to former ranges, raising chicks in captivity and releasing them into the wild—a process called hacking.

Volunteers cleaned up lead-shot carcasses, while utilities redesigned power lines to curb electrocutions.

By 1995, the Bald Eagle climbed to “Threatened” status, and in 2007, it flew off the endangered list entirely.

Today, over 71,400 nesting pairs thrive in the U.S., with Alaska alone hosting 30,000 Bald Eagles.

Canada and Mexico bolster the total, pushing North America’s population past 100,000.

The Bald Eagle’s roar—or rather, its shrill cry—now echoes from coast to coast, a recovery hailed as a conservation masterpiece.

Ongoing Challenges and Efforts

The Bald Eagle isn’t out of danger yet. Habitat loss from urban sprawl and climate change threatens nesting sites, while lead poisoning persists—studies show 10-15% of Bald Eagles still suffer from it.

Invasive species and oil spills, like the 2010 Gulf disaster, endanger coastal populations.

The Bald Eagle also faces wind turbine strikes, a modern hazard in its flight paths.

Groups like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service monitor the Bald Eagle, enforcing laws and educating hunters to switch to non-lead ammo. Sanctuaries—like Minnesota’s National Eagle Center—rescue injured Bald Eagles, releasing them once healed.

Citizen scientists track nests via webcams, offering real-time glimpses into the Bald Eagle’s life.

These efforts ensure its resurgence holds strong, keeping the Bald Eagle a fixture in the wild.

Final Note

The Bald Eagle embodies more than a bird—it’s a saga of survival, a keystone of nature, and a beacon of hope.

Biologically, the Bald Eagle dazzles with its size, vision, and adaptability, hunting fish and scavenging with equal skill.

Ecologically, it balances ecosystems, its presence a sign of clean rivers and robust prey.

Culturally, the Bald Eagle reigns as America’s emblem, its white head soaring through history from Native ceremonies to the Great Seal.

Its journey from near extinction to thriving abundance proves what’s possible when humans act.

The Bald Eagle once faltered under DDT and guns, but today, it graces skies from Alaska to Florida, a recovery fueled by bans, laws, and love for the wild.

Challenges linger—lead, habitat loss, climate shifts—but the Bald Eagle’s resilience shines through, mirrored in nests that grow yearly and wings that span horizons.

Spotting a Bald Eagle—its silhouette banking over a lake or its cry cutting the silence—stirs something primal.

It links us to a prehistoric past, when its ancestors ruled ancient skies, and to a future we can shape.

The Bald Eagle isn’t just a symbol of freedom; it’s a call to protect the wild places it calls home.

As it glides above, the Bald Eagle reminds us: strength endures, beauty persists, and with care, nature’s kings can reign on.

Frequent Questions and Answers About Bald Eagles

Question: How long does a bald eagle live?

Answer: In the wild, bald eagles typically live 20 to 30 years. In captivity, some have reached up to 50 years thanks to consistent food and care, but wild eagles face more risks like predators, accidents, and food scarcity, so they don’t live as long.

Question: How do you determine a bald eagle’s age?

Answer: You can tell a bald eagle’s age by its plumage until it’s about 5 years old—juveniles have mostly brown feathers, which gradually turn into the white head and tail of adults. After 5 years, when they are fully mature, their feathers don’t change much, so aging them becomes nearly impossible.

Question: Does the bald eagle mate with different kinds of eagles?

Answer: No, bald eagles stick to their own species. They don’t crossbreed with other eagle types, like golden eagles, in the wild.

Question: Do bald eagles have only one mate for life?

Answer: Usually, yes—bald eagles are monogamous and often stay with one partner for life. But sometimes, an outsider (usually a female) challenges one of the pair for the territory and mate, occasionally winning it. If one mate dies, the surviving eagle will find a new partner and typically stay in the same nesting area.

Question: Do eagles push their young out of the nest to encourage them to fly?

Answer: No! Bald eagle parents don’t force their eaglets out. As the young near fledging age (10–12 weeks), adults might withhold food to nudge them toward a nearby perch for a meal, but most eaglets are eager to try flying on their own—no push needed!

Question: If an eaglet falls, will a parent fly below the nest to catch it and carry it back?

Answer: No, bald eagle parents won’t swoop down to catch a falling eaglet. If one falls before it can fly, it’s usually stuck until it fledges or, sadly, may not survive.

Question: Do bald eagles build their nests in low trees?

Answer: No, bald eagles don’t choose low trees. They prefer tall “super-canopy” trees—ones that tower above others—with strong branches and a clear view of the land and water nearby. Nests are typically 50 to 125 feet high, always close to a river, lake, or coast.

Question: How tall do trees have to be for a bald eagle to nest in?

Answer: The taller, the better! Bald eagles like trees at least 50 feet high, but they’ll pick ones up to 125 feet or more if available, as long as they’re sturdy and near water.

Question: Why do bald eagles have such big nests if they only have two eggs?

Answer: Bald eagles build huge nests because they’re big birds—adults have wingspans over 6 feet—and their eaglets grow large, too. The nest needs space for the parents, their two or three chicks, and all those flapping wings as the young prepare to fly.

Question: About how long does it take for the bald eagle’s eggs to hatch, and how long until it can fly?

Answer: Bald eagle eggs hatch after about 35 days. The eaglets stay in the nest for 10 to 12 weeks before they fledge, meaning they take their first flight from the nest.

Question: How old are young eagles before they can fly?

Answer: Young bald eagles can fly at 10 to 12 weeks old, when they fledge and leave the nest for the first time.

Question: When do eagles learn to fly and how?

Answer: Bald eagles start flying between 10 and 12 weeks old when they fledge. They practice by making short flights to and from the nest and nearby trees, getting better over the next 1 to 2 months with their parents nearby.

Question: How old does a baby eagle have to be to leave its mother?

Answer: Baby bald eagles leave the nest at 10 to 12 weeks old when they fledge. After that, they often stick around for another 1 to 2 months, learning to fly and hunt with their parents’ guidance before heading out on their own.

Question: How long does it take the eaglet’s feathers to turn brown?

Answer: An eaglet’s feathers are brown from the start! They begin growing feathers around 5 weeks old and are mostly fully feathered by 9 weeks—no turning needed, as they’re born with that juvenile brown look.

At Facts and Tips, we strive for accuracy and honesty.

If you notice any errors, whether factual, editorial, or outdated information, please don't hesitate to contact us.

Found this article about Bald Eagle informative and useful? Share it with your friends and colleagues—they might find it helpful too!